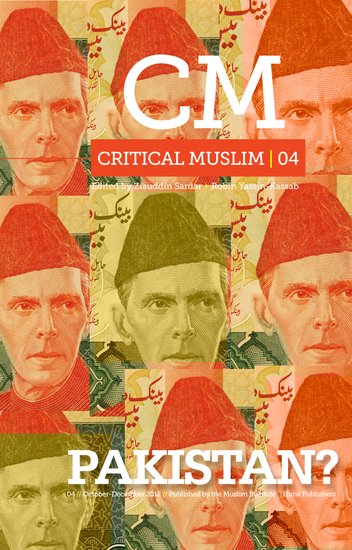

From Critical Muslim 4: Pakistan? (Hurst, London, 2012)

Like the sword of Damocles, a perennial question mark hangs over Pakistan. Can Pakistan survive? Can it continue to endure the ‘war on terror’? Will it see out drone attacks, the Taliban, violent fundamentalists, the insurgency in Balochistan, inter-provincial rivalries, rampant corruption, economic meltdown and twenty-hour daily electricity blackouts? Given that it ranks high on the Failed States Index and is characterised by ‘perversity’, US-based journalist Robert Kaplan goes as far as to phrase the question as: should Pakistan survive?

No, is the proper answer, according to US military analyst and novelist, Ralph Peters. ‘Pakistan’s borders make no sense and don’t work’, Peters testified before the US House of Representatives Committee on Foreign Affairs. Instead of ‘defending the doomed relics of the colonial era’, the US should actively promote the balkanisation of Pakistan. In his testimony Peters suggests that Pakistan should be divided into a Free Balochistan and a Pakhtunkhwa for all Pashtuns – ‘despite their abhorrent customs’. One presumes that by this logic there should also be a Sindhistan for all Sindhis, leaving what’s left of Pakistan to the Punjabis. According to yet another expert, Michael Hughes writing in The Huffington Post, a fragmented Pakistan will be ‘easier to police and economically develop’ and thus its ‘rapid descent towards certain collapse’ could be avoided. In this best of all possible worlds, breaking Pakistan into small pieces is necessary to ‘fix it’.

Questions arise, and are asked, in a context. There are good reasons why certain questions should be asked about Pakistan. However, questions, by their very nature, can also lead to a restricted set of answers. When a question is framed in such a way that an answer, or a set of specific answers, becomes inevitable it serves not as inquiry but as ideology. ‘Can Pakistan survive?’ has only two possible answers: yes it can, no it can’t. Either answer frames Pakistan as a problem now and for the future. US policymakers asking the question perceive the problem to be that Pakistan cannot be ‘policed’, managed and controlled, which is what makes it ‘perverse’. By equating Pakistan with survival, the question automatically consigns Pakistan to history. The country becomes an entity whose survival is permanently at issue, an insoluble problem. Implicitly, it is a problem that needs to be feared. So we move naturally to the next question: ‘should Pakistan survive?’

This is essentially an ethical question based on the assumption that as a problem to be feared perhaps Pakistan ought not to survive. The stark fact that Pakistan is still there, despite numerous predictions of its imminent demise by countless pundits, does not affect the logic of these questions. Certain questions are thus not questions at all. To answer them is to reinforce the assumptions they are based on and accept these suppositions as self-evident truths. Questions about the survival of Pakistan are in fact an act of violence towards an already beleaguered nation. The best response to such inquiries is provided by the Victorian poet Robert Browning:

Well, British Public, ye who like me not,

(God love you) and will have your proper laugh

At the dark question, laugh it! I laugh first.

So, what then are the appropriate questions to ask?

Let’s begin with: why are things the way they are? The crisis in Pakistan is certainly a product of what Ayesha Siddiqa, the Islamabad-based security analyst and author of Military Inc.: Inside Pakistan’s Military Economy, calls a ‘chain of deep state’. It consists of an alliance of the military, the feudal landlords and the politicians. Pakistan’s military is not just a conventional army but also a corporation, which produces all varieties of goods and services from soap and banking to cornflakes and housing development. Its main concern seems not so much to defend the country, on which its record is rather poor, but to maintain and enhance its business interests. The military siphons off a sizable chunk of the country’s revenues and virtually all of its foreign aid. Its spy arm, the Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI), is above the law and human decency; it has become a murderous institution that has targeted not just dissidents but also human rights lawyers. Both the military and the ISI have nursed and nourished the Taliban, promoted extremists and violent organisations, and supported al-Qaida. Pakistan is an agricultural state; around half of its GNP and most of its exports are based on agriculture. The feudal landlords, consisting of a few thousand extended families, control the bulk of Pakistani agriculture. The land is worked by peasants or tenants who are virtually in bondage to the landowners. To preserve their wealth and privilege, the feudals fight hard to keep the landless peasants on their fiefdoms uneducated and dependent. Both the military leadership and the politicians come from this feudal class of Zamindars, Jagirdars, Nawabs and Vaderas. Political parties are structured on feudal patterns and led by feudal leaders who run them as their private property, passing on what they regard as inheritance to their children. Pakistan Muslim League, the party that established Pakistan, was dominated by feudal lords from its inception. The Pakistan People’s Party is the fiefdom of the Bhutto family. President Asif Ali Zardari has already declared that his eldest son, Bilawal Zardari Bhutto, will succeed him as Chairman of the Party. The bulk of the lower house of parliament, the National Assembly, consists of feudal landlords; there are certain individuals from this background who always win elections – no matter what. Key posts in the executive also go to the feudals. The army itself has evolved a feudalist structure. Much of the judiciary too comes from the same feudal class. So the same group of families are in power whether the country is ruled by a military dictator or sustained by an illusory democracy.

The ‘deep state’ uses Islam as an instrument to maintain the status quo. Allegedly, Pakistan was created in the name of Islam. But Islam in Pakistan is not a faith or a worldview but an ideology. Like all ideologies, it is an inversion of truth: whereas Islam, in theory at least, is about justice and equality, in Pakistan it functions as a mechanism for oppression. In other words, it has gone toxic. While Islam values mercy, forgiveness, compassion, pluralism and diversity, in ‘the Land of the Pure’, ideological Islam has jettisoned all that is humane. Almost everything that carries the adjective ‘Islamic’ in Pakistan is associated with puritanism, intolerance, chauvinism and phobia of the Other. Women, the Shia, the Ahmadis, Christians and Hindus are all harassed and killed in the name of Islam. Suicide bombers kill countless innocent people to promote their Islamic cause. All the elements identifying themselves as ‘Islamic’, from religious seminaries to political parties such as Jamaat-e-Islami and various brands of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam, to the outright psychotic groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba, Sipah-e-Sahaba, Khatm-e-Nabuwat and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, have authoritarian or semi-fascist tendencies. For those with little hope, Islam serves to provides a sense of moral superiority, a brand of soap that washes whiter than white.

The irony is that the brand of Islam which has become dominant in Pakistan is no friend to the poor and the marginalised. It is an aggressively capitalist and ugly enterprise, a natural ally for the conservative middle class by which it is eagerly embraced. This toxic Islam is one of the biggest hurdles to land reform in the country. One would expect the feudal landlords to be against reforms of any kind. On numerous occasions when efforts have been made to tackle land reform, the feudalists have argued that the problems of the peasants are their own creation, hence land reform could actually increase their plight. Despite resistance from the feudal quarters, land reform has been undertaken in Pakistan under various governments in 1959, 1972, and 1977. Limits have been introduced on how much land can be owned by individuals. Millions of acres of cultivated land were redistributed. It was a small, incremental advance. But in 1986, the Federal Shariat Court, created by the military dictator Zia-ul-Haq with ‘specific authority to carry out judicial review of all laws’ and ensure they were not ‘repugnant to the injunctions of Islam’ declared that a ceiling on land holdings was un-Islamic. In a famous August 1989 judgement (Qazalbash Waqf v. Chief Land Commissioner, Punjab and others), the Federal Shariat Court ruled further that the Shariah places no limit on the land that can be owned by a feudalist. Moreover, the state is not obliged to spend any surplus on the poor. So Islam is specifically constructed in Pakistan as an instrument that promotes feudalism and oppresses the poor and the marginalised. Shariah rules OK. The poor and landless peasants are only there to shout slogans at demonstrations against blasphemy or some other perceived insult to Islam, and serve as cannon fodder for the Jihadi groups.

Despite the suffocating stranglehold of the ‘deep state’ and the poison of toxic Islam, Pakistan is still there. An appropriate question would be: why has Pakistan not disappeared into a black hole? How does it manage to survive? Or as the German philosopher Martin Heidegger would say, why is there something rather than nothing?

Equipped with a few tomes and a few sentences of Urdu, Robin Yassin-Kassab sets out to answer this question. He travels by bus, rickshaw and plane from Karachi to Bahawalpur, Lahore and Islamabad. He attends literary festivals, joins protest rallies, participates in Sufi dance sessions, and talks with intellectuals, academics, writers, politicians, journalists, ordinary citizens and the occasional ‘naked madman’. He is quite overwhelmed by the diversity and complexity of Pakistan; it is certainly not a place that can be seen through a single lens, say that of religion or the Taliban. Good and bad things are happening simultaneously:

Pull up at the lights and there’s a disabled child (possibly kidnapped and then tortured)

begging, or a boy washing the windscreen, or a man making a monkey clap

for a few rupees, or a man banging a drum. Alternatively park at some shop fronts,

wind down the window, order some samosas or juice, and watch the people buying

and selling, joking and fighting, singing and praying, smoking and snoring. And

playing cricket, for Pakistanis are playing cricket wherever you cast your gaze.

The real strength of Pakistan, concludes Yassin-Kassab, is the resilience of its people, who always find the inner resources to rise above the turmoil. The state may be weak, but societies are strong. The country may be ruled by one of the most corrupt governments in its history, yet it does function as a democracy. It is being torn apart by violence, yet somehow held together by men and women who value peace and integrity. Instead of looking for scapegoats to blame, Yassin-Kassab suggests we should find time to praise its people. ‘The country is overflowing with the bright and the beautiful.’

Of course, not all the people of Pakistan are praiseworthy. Karachi, major port and economic hub, is plagued with a culture of political violence and the antics of vicious gangsters. The city, as Taimur Khan notes in his brilliant excursion into its underbelly, is enveloped with fear and foreboding. Khan takes us to the parts of the city that are largely invisible not just to outsiders but also to most of Karachi’s inhabitants. In Lyari we meet the gangsters who run protection rackets but who also hope for better education and amenities for their neighbourhood. In De Silva Town, Khan spends some time with a taxi driver caught in ethnic violence and plays pool with members of the Christian community. We meet the body builders of Federal B Area and the bookies and the violent land developers and property magnates of Guru Mandir. In Karachi, ‘there is room for everyone.’

There is also hope. Khan asks Imran, a young high school student from Qasba Colony, if he would like to live somewhere else? ‘I never want to live anywhere else but here’, Imran responds without hesitation. Why would a young man wish to live in city noted for its lawlessness, political and ethnic violence, targeted killings and culture of fear? Perhaps because there are other things in Karachi the young man values. Karachi is noted for its entrepreneurial spirit. Wherever you look, says the journalist and activist I A Rahman, ‘everybody, from a coolie to an industrial baron, is engaged in utilising all his time to do something.’ The inhabitants of the city place a high premium on time.

The public dismay at any enforced suspension of work — caused by a call for hartal (strike) or disruption of power supply — is to be seen to be believed. Whenever a strike is called, workplaces have to be closed and vehicles kept off the roads to avoid heavy losses. But everyone remains keen to break the ban. As the evening approaches and the vigilantes retire to report success to their superiors, the vendors rush to their posts, shops reopen and streets come alive with fast-moving, noisy traffic.

Karachi is also a city that takes social service, charity and philanthropy seriously. Indeed, I have been out with the volunteers who manage the ambulances of the Edhi Foundation, which provides the only viable emergency service in the city. I have seen the dedication and passion of the citizens who organised the Orangi Pilot Project, and worked tirelessly to build schools, improve drainage and water supply, set up micro credit schemes, and establish health facilities in a million-strong shanty town. I have visited the schools built by a charity called The Citizens Foundation; and the offices of the Urban Resource Centre, which highlights the problems of the city through research and documentation. All of these institutions are run by the kindness of donors and the generosity of volunteers.

In Peshawar civic culture is not as strong as in Karachi. As elsewhere in Pakistan, the ruling party in Peshawar, the capital of the northern province of Khyber-Pakhtunhwa and the administrative centre of the Federally Administrated Tribal Areas (FATA), is using its ‘power as an extended opportunity to seize patronage from the state and distribute it to its supporters’. More and more wealth, notes Muhammad Idrees Ahmad, is being ‘squirreled away into gated communities of extraordinary opulence’. Even railway tracks are not spared by thieves. Idrees revisits the city of his birth after several years of absence to discover that the employment situation has become so bad that labour is forced to migrate to Afghanistan. There is a great deal of sexual frustration amongst the youth, ‘instances of child abuse are frightfully high’, and oppressive tribal traditions continue to make life difficult for most people. Yet, there is hope in Peshawar too. The ‘dignity, hospitality, generosity, irreverence, humour, compassion and grace under pressure’ of the people of Peshawar ‘remain matchless’. There is a dynamic women’s movement, a broader awareness of political issues, and the city’s culture of self-sacrifice is alive and thriving.

Life in Quetta, the provincial capital of Balochistan that borders Afghanistan, is even more precarious. Quetta provides a good illustration of the mindboggling ethnic diversity of Pakistan. Mahvish Ahmad visits the city at considerable risk to herself and discovers an ethnically divided city ‘under attack from all sides’. The ethnic communities of the city, the Pakhtuns, Baluch, Hazaras, Punjabi and Urdu-speakers, ‘live in their own exclusive enclaves’. The city is ‘a thoroughfare for food and weapons to NATO forces across the border and the headquarters of the notorious Taliban Leadership Council’. There is a constant shadow of imminent violence from the ‘war on terror’, ferocious extremist groups, the Baloch groups fighting for secession, and Pakistan’s paramilitary Frontier Corps constantly on the lookout for ‘suspicious’ individuals. Ahmad visits a graveyard where the bodies of Hazara victims of the extremist group Lashkar-e-Jhangvi lie: ‘bodies were buried in straight lines, with the same headstones inscribed with the same dates.’ Ahmad tracks down Baloch separatists who claim to be secular and progressive and feel frustrated at being ignored and marginalised. They complain about the domination of ‘treacherous Sardars’, the tribal leaders, and blame the government for pitting the ethnic minorities of the city against each other. She talks to Pakhtun leaders who want Balochistan to split into two provinces, so they can have their own province and their own governance. Both sides use history to justify their claim to dominate and control the provincial capital city of Quetta.

The relevant question for Quetta is not who is a Baloch, a Pakhtun, or Hazara but who is a Pakistani. While questions of ethnic identity are obviously important, they seldom lead to a viable, inclusive politics. What confines peoples’ thought, and limits their scope for action, are the questions they consistently ask themselves. Questions based on fragmented and isolationist ideas can only produce yet more fragmentation and isolation. To change one’s outlook on life, to move from despair to hope, one needs to ask bigger questions. That’s why Ahmad’s suggestion that all sides in Quetta come together in a new secular alliance, based on the model of the old National Awami (People’s) Party (NAP), makes sense. NAP, a united alliance of all ethnic groups in Balochistan, advocated provincial autonomy, recognition of different ethnic groups as ‘nations’ and demanded certain rights on the basis of ethnicity. Such an alliance, based on a progressive politics, could provide true hope for the troubled people of Quetta and Balochistan.

Merryl Wyn Davies is concerned with perhaps the biggest question of all: what is Pakistan? To the first-time visitor it is a place known through received ideas: myths, legends and innumerable stories, many represented in the work of artists or portrayed in cinema and on television. None of these, apparently, include mention of peaches. Davies travels to the small North West Frontier village of Pir Sabaq, devastated by the great flood of 2010. What she discovers is totally unexpected: despite great odds, the people of Pir Sabaq have rebuilt their village and their lives. Davies is moved by the courage, resolve and the will to succeed demonstrated by the women of the village. From the disjunction of her expectations of the North West Frontier and the encounter with peach orchards, Davies begins a reflection on the power of imagined landscapes. In her travels she encounters a variety of ‘imaginariums’, coherent world pictures each laying claim to being the reality of time and place that once was and now comprises Pakistan. She is aware not only of a plurality of imagined worlds but the tenacious hold even the most discredited ideas have on her expectations. She notes the subtle way in which Pakistan as a newly created country dislocates the past. To India belongs antiquity and heritage, to Pakistan the predicaments of modern politics. This newness, she argues, even affects the investigation of the most ancient past, the remains of the Indus Valley civilisations found within Pakistan. Imagined landscapes, Davies suggests, do not evaporate in the face of contradictory reality. The real potency of imaginariums is their power to influence and direct response in spite of reality, their ability to cause people to act and react as if what was imagined and expected is, nevertheless, actual. The question is not which imagined world is right, nor what is the correct answer. Imagined landscapes, the idea of a place, is always multiple, seen with different expectations of past, present and future by everyone. What is important is acknowledging and accepting the coexistence of these multiple realities. The Pakistan Davies finds is a compound reality in which whole galaxies of imagined landscapes are in play and all exert their influence. It is in tracing the outlines of imagination for the variety of people and place she encounters that Davies finds that complex location called ‘Pakistan’.

This complex Pakistan has an abundance of intellectual and cultural resources that provide us with hope and inspiration. Take Pakistan’s media: a phenomenon to behold. Numerous television channels, such as Geo TV, ARY, Dunya and Samaa, writes Ehsan Masood, are ‘relentless in their coverage of corruption, and in their dogged questioning of officials, including the army’. Not surprisingly, many journalists have paid a heavy price for their bravery: from being roughed up by police to murdered by the intelligence services. But despite the threats and intimidations, ‘no politician of any party can expect an easy ride from journalists’. They are grilled not just in a plethora of daily talk and analysis programmes but also mercilessly lampooned in razor-sharp satirical shows. Then, of course, there are what Pakistani viewers call the ‘dramas’, the soaps, mostly focused on cultural, social and political issues, and largely designed to be a mirror to society. Quite simply, these dramas, which can run as serials for months if not years, are among the finest and most hopeful things Pakistan has to offer. They can, and often do, bring entire cities to halt, generating intense debate and discussion. Freedom, in the domain of the media or elsewhere, often has its consequences. Masood highlights some of the recent amusing and not-soamusing scandals of the media, and the travails of Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority (PEMRA), one of the few institutions in Pakistan seemingly not short of cash. Regulating hundreds of channels would be a nightmare for any regulator even in a highly developed country. For PEMRA, with all its resources, ‘trying to regulate Pakistan’s new electronic media is like trying to be the sheriff in a cowboy movie.’

One reason why Pakistani television dramas are so apt and brilliant is that they are, as Aamer Hussein shows, either based on classical Urdu novels or written by mostly female successful writers. Hussein relates how, as a young adult living in London, he discovered the ‘house of treasures’ that is Urdu literature. He began by laughing at the prose of Razia Butt’s novel Saiqa – ‘lushly descriptive of landscape and emotions alike, the situations lachrymose’– but soon realised that ‘the world-behind-a-curtain Butt portrayed was far closer to the lives of most of her young readers than our “modern” way of living or our anglicised tastes.’ He moves on to A R Khatoon’s Nurulain and remembers that his mother used to read this story to him when he was seven. Through Hussein’s personal story, we discover the great works of modern classic Urdu fiction, most of which chronicle ‘the struggle for justice and human compassion throughout history’. A charming story from Khatoon’s Kahaniyan, ‘Princess Mahrukh and the Magic Horse’, is included in this issue of Critical Muslim. Mahrukh is a headstrong princess who receives a horse as a gift from her father, but the horse is only a horse by day and becomes a seductive prince by night. When the horse prince elopes with her slave girl, Mahrukh follows his tracks through inhospitable terrain before she reaches the land of Kanggan, where she avenges herself.

Hussein briefly mentions one particular writer who is as indigenous to Pakistan, and as ubiquitous as paan (a betel leaf concoction). The nation’s answer to Ian Fleming is one Ibn-e-Safi who at the peak of his productivity produced two detective novels a month. His most famous series are Jasoosi Duniya (The World of Spies), which began in 1952, and Imran Series, which first appeared in 1958. Ibn-e-Safi, who suffered both at the hands of the British and Indian authorities because of his progressive views, wrote 232 novels in all. He kept a whole generation of Pakistanis, including myself, enthralled right up to his death in July 1980. He appealed equally to the

young and the old, and the story of his life and works is told through another story: the discovery of a fake Ibn-e-Safi (yes, in Pakistan they can fabricate anything, including novels) by my grandfather, Hakim Abdul Raziq Khan, in the small town of Bahawalnagar, where I grew up.

Ibn-e-Safi and the writers discussed by Hussein are the literary heroes of my generation, but Pakistan is also blessed with a new generation of equally inspiring writers. Bina Shah asks the question: is there a boom in Pakistani literature? If so, is it something genuine and deep-rooted or something that will eventually fizzle out? Certainly, talk of a boom makes little sense if the focus is on the so-called ‘Corona of Talent’, invented by Britain’s literary magazine Granta. The ‘Big Five’ are said to be Kamila Shamsie, author of Burnt Shadows; Mohsin Hamid, whose The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2009) is being made into a film; Mohammad Hanif, who wrote A Case of Exploding Mangoes (2009); Nadeem Aslam, the writer of Maps for Lost Lovers (2005); and Daniyal Mueenuddin, whose collection of short stories In Other Rooms, Other Wonders (2010) has been much praised.

Shamsie has been writing for two decades, which hardly qualifies her to be ‘new talent’. I encountered her in 1998, when her first novel In the City by the Sea came out, around the same time as I was regaling myself with Aamer Hussein’s stories in This Other Salt (1999). Aslam, in contrast, is likely more British than he is Pakistani. And Daniyal Mueenuddin has yet to make himself heard outside a small circle of English-speaking writers and editors. Some of these writers display a tendency towards stereotyping women and falling back on lazy ‘terrorism’ narratives, which Shah dissects. If this ‘corona’ is compared to the writers considered by Hussein, the boom turns out to be not much louder than a fire cracker.

Literature is indeed thriving in Pakistan but rather like the ‘New World’ of Columbus, it has always been there, and did not need ‘discovering’. In literature, as in other fields, constructed imaginariums and the limiting logic of the questions they promote serve as traps that prevent us from seeing the whole picture. Pakistani literature, as Shah rightly says, is ‘a longstanding movement with history and depth’. Indeed, one may find generations of writers in one family as Muneeza Shamsie, Kamila’s mother, shows in her essay ‘Discovering the Matrix’. It’s a tradition that nurses, nourishes and provides hope. And represents ‘the long and continuous struggle of Subcontinental women to assert their voice and claim their right to speak’.

However, it is not just literature that is flowering in Pakistan. The country’s truly phenomenal tradition of music continues to flourish. No one in Pakistan, writes Bilal Tanweer, ‘needs to be told What Coke Studio Is and What It Does’: its status as ‘a cultural behemoth’ is confirmed. Since it was first broadcast on TV in June 2008, Coke Studio has been a sensation. What it does is profoundly simple: it synthesises tradition and modernity in ‘a clear attempt to bridge the cultural fragmentation of Pakistan’. And it succeeds.

Literature and music, the foundations of culture, can be a great source for healing a nation. But Pakistan needs to change its politics too. Here, some hope is offered by Imran Khan, the celebrity cricketer turned charity fundraiser, who has discovered latent charisma now as a politician. Khan, in Ali Miraj’s assessment, ‘has captured the zeitgeist’. He has managed to mobilise tens of thousands of young volunteers (with some assistance from music), and speaks their language. Miraj is impressed by Khan’s clean record, probity and determination; but he is also troubled by his religious zeal, naked nationalism and naïve analysis of the problems of the nation. On the whole, he offers a ‘real alternative’ to the ‘dynastic merry-go-round of the Bhuttos on the one hand and the Sharif brothers, the leaders of the Pakistani Muslim League (N), on the other, with smatterings of military rule in between’. He has articulated an ‘attractive vision of a country based on meritocracy rather than nepotism’. However, we would be unwise to put all our proverbial eggs in one basket. Khan, as Miraj notes, faces tremendous obstacles: from the ‘Obama syndrome’ of promising too much and delivering little, to dirty politics; entrenched operators; the feudal structure of Pakistani politics to the threat of assassination. If Khan fails, there will be others to fill his shoes.

However, no action can be undertaken if individuals or nations are suffering from a mental paralysis. As Taymiya R Zaman discovered, certain questions allow no room for sensible answers. Constantly bombarded by her American students with questions, which were actually aggressive statements about the failure of Pakistan, Zaman retreated into herself and refused to talk about her country. She was so paralysed that she was not even sure of her own feelings about Pakistan: ‘the sheer fatigue of deflecting questions left me with little room to know what it was I would say if allowed to speak on my own terms, or even what these terms would be.’

Like Zaman, Pakistan too seems to be paralysed by questions constantly thrown in its direction by America and the way it is framed in the West. Most Pakistanis blame the US for all the country’s problems. There is, indeed, a great deal to blame, not least the fact that the US has dragged Pakistan into its ‘war on terror’ and continues to order drone strikes on Pakistani territory, very likely in contravention of national and international laws. If the two countries weren’t supposed ‘allies’, then the actions of US military commanders would in effect be tantamount to a declaration of war on a sovereign nation. But America is an imperial power, and imperial powers do not have friends, they have only ‘interests’. The main religion in America is an aggressive notion of ‘national security’, a cult of death of which robotic killing is the latest fetish. So it is delusional to believe that America can be a friend of Pakistan. Equally, being paranoid about America, or perpetually looking for conspiracies (a favourite pastime for Pakistanis), can be fatal for Pakistan. Nothing consumes one more thoroughly or easily than hatred of something over which one has little power.

Zaman’s paralysis is only cured when she visits Pakistan on a sabbatical. The ‘images of suffering, helpless brown people waiting for Angelina Jolie’s benevolence’ evaporate. It was ‘like running into the arms of a lover you’ve been forbidden to see for years’. There was nothing menacing about the immigration officer; students in Lahore are more amiable and trusting than their American counterparts; and she felt safer in the streets of Karachi than San Francisco. In Lahore, she comes face to face with the real Pakistan and has an epiphany:

A woman is walking in our direction, obviously agitated, pounding on car windows.

She comes to Haniya’s window and raps on it. Haniya rolls her window down. The

woman says her sister has been burned in an accident and she needs to get her to

the hospital. Will we help her get the road open? ‘Yes,’ we say. Car doors open,

women and men rush out into the night. The woman argues with the police. The

crowd backs her up. The policemen say they are doing their job. ‘Is this politician’s

life worth more to you than my sister’s?’ she yells. They seem shamefaced. The

crowd gathers momentum. A man says he is recording this because he is a journalist

from GEO. The policemen open the road. This is the Pakistan I know and love, I’m

thinking. These ordinary victories, nothing short of heroic. When the long-awaited

winter fog descends on Lahore, I am convinced that the city is magic, and the magic

is compounded because it will never make it to newspapers abroad. This magic is

ours, you think, disappearing into the night with your secret lover, and no one

needs to know.

Self-discovery. That’s what liberates Zaman and restores her true self. Pakistan too needs to discover itself and reflect on the testimony of the magic of its societies and the heroic deeds of its ordinary citizens. Pakistan needs to consider what determines the fate of nations. Can a nation exist as a surrogate of an imperial power or can it determine its own destiny? Ultimately, Pakistan’s problems are its own creation; and only Pakistan can solve them. The country is in dire need of questions that focus the mind towards self-reliance and self-assertion. Those who live in history look backwards; they can only repair their self-image by imagining that they are morally superior to others. A better way for a nation to improve its self-esteem is to correct its deficiencies, to reorient itself by ditching obscurantist dogma and reinventing tradition; rebuilding with the resources of heritage and culture is a much bigger challenge.

The question all Pakistanis should be asking is: what can be put right? Or, more appropriately, what can we put right? The answer is: almost everything; and every segment of Pakistani society has a share of responsibility. Take the military. How can an army protect its own people when it becomes a cancer on society, consuming its host? Where would that leave the military itself? Or take the issue of Balochistan. Would it not be better to grant Balochistan, and other ethnically-based provinces, full autonomy? Would this not only give them the freedom they crave and remove the torment of Punjabi majority domination, but also redirect the energies wasted in ethnic struggle and violence towards building civil society? Central authority imposed by force never works; rather, central authority is effective only if it is clearly demarcated.

Numerous other options become possible provided the civilian elite begins to pay in tax what it owes and realises that stealing from the nation is against its own self-interest and will eventually lead to its own demise. A country cannot develop or maintain its infrastructure or function as a viable state unless its citizens pay their taxes. The need for infrastructural improvements in Pakistan is verging on the cataclysmic. Roads are crumbling, the railway is over a century old, large segments of the rural population are not connected to electricity grids and water supplies, the sewage systems are overwhelmed, and the national airline is too expensive for domestic and too unreliable for international travel. Pakistan needs to rebuild its public transportation system and invest in railways. Power is not only unreliable, it is also very expensive. There is an over-reliance on a handful of very old dams, and a couple of ageing nuclear power plants. Yet, there is plenty of potential for solar and other renewable sources of energy. Why isn’t Pakistan investing more in alternative sources? Of course, it would help if the army, which has siphoned off much of the country’s wealth, and the feudal landowning elite, who have looted the nation for decades, paid their outstanding energy bills. The country also needs serious measures to stop deforestation which is among the reasons for the floods we have witnessed in recent years.

But citizens have responsibilities too and there is much evidence that, regardless of the failures at the top, these are being taken seriously. In many cities, citizens are delivering services where the state is failing, for example establishing schools as in the case of The Citizens Foundation charity; encouraging alternative sources of energy supplies as the many environmental groups are doing; or organising sanitation and waste collection, pioneered by the world-changing work of the late Akhtar Hameed Khan, who founded the Orangi Pilot Project.

This is closer to the reality of Pakistan than what you might read in an essay in The New Yorker or in Granta and this is the reality we have tried to convey in this issue of Critical Muslim. Our stories are by no means complete because we, too, are mostly outsiders rather than participants in the nation’s daily life. And, like all observers, we too flew into the nation’s airports with pre-conceived ideas. But, as Yassin Kassab, Davies, Zaman, and the Londonbased comedian Shazia Mirza have all shown, we were willing to have our own baggage challenged, opened up, replaced, or thrown out.

Mirza in particular had no hesitation in shattering her perceptions of a country, ‘famous for Imran Khan and terrorism but not comedy’. ‘There was no shouting or fighting or war of any kind,’ Mirza writes, tongue firmly in cheek. Perhaps most surprising of all, she discovered that Pakistanis laugh at bawdy sexual jokes. ‘I should never have listened to people who kept telling me, “don’t tell jokes about sex, politics, religion, terrorism, or news”’, Mirza declares.

Pakistan too should stop listening to people who triumphantly announce its collapse, or to those who childishly describe it as a ‘cartographic puzzle’. Instead, it must continue to ask questions of its own, and continue to demand answers from its rulers and from its paymasters. If you internalise what imperial power says about you and play dead, you should not be surprised to see vultures circling above you.

Pakistan needs only to listen to itself. And ask questions that matter.